Beachcombers' Guide to Keats Island Shells

Welcome! This is a guide to identifying the most common shells that can be found on the beaches of Keats Island, British Columbia. There are nine common bivalves (shellfish) that leave their shells on Keats Island beaches, and six common sea snails. This guide will walk you through how to identify these species. Keep in mind that while the vast majority of seashells on Keats Island will be one of the species covered in this guide, there is always the chance of finding something rare! If you aren't sure what something is, post the photo to iNaturalist and experts can help you identify it.

Before we get into the species, here are some tips when getting started. If you're already familiar with shells, feel free to skip to the species entries below!

First, some basics: there are three main types of animal that leave shells on Keats Island: barnacles, snails, and bivalves. Bivalves include clams, oysters, and similar animals, and their shells have two halves. The spot where the two halves are attached is the hinge, and the details of the bumps on the inside of the shell near the hinge are often very important for identification. The two halves of the shell are often different at the hinge, so this is important to keep in mind when comparing shells. When taking photos of a shell for identification, aim to take a closeup of the hinge. Also take a photo showing the inside of the shell, the outside of the shell, and a side view showing the sillhouette (showing how flat or curved the shell is).

Acorn barnacles

Barnacles are not related to the other seashells in this guide, but I couldn't include a guide to Keats seashells without mentioning them. While the rest of the species in this guide are mollusks (related to snails, slugs, octopi, etc), barnacles are actually crustaceans, more closely related to crabs than they are to mussels and clams. The most ubiquitous barnacle on Keats Island is the Pacific Acorn Barnacle, which forms a ring on the rocky bluffs just above the blue mussels. This contributes to the stripey look of our coast from a distance: first bare grey rock above the high tide line, then a white ring of barnacles at the high tide line, followed by the deep blue ring of mussels below. These small white shells will be familiar to any beachgoer who frequents the rocky shores, and can be painful to bare-footed beachgoers!

Blue Mussels

Blue mussels are the most ubiquitous seashell on Keats Island. They attach themselves to the rocky bluffs that encircle the island, forming dense colonies that can be seen as a distinctive blue-black ring around the island, just below the grey ring of barnacles. Where their shells accumulate in large numbers, the fragments can make the entire beach look blue from a distance.

Their blue colour and elongated shape make them easy to differentiate from other seashells, but despite being our most common shells, our blue mussels are actually considered impossible to identify to species without laboratory tests! This is because there are three species of blue mussel that look essentially identical: Mytilus trossulus, Mytilus edulis, and Mytilus galloprovincialis (you can find more information here: https://www.centralcoastbiodiversity.org/pacific-blue-mussel-bull-mytilus-trossulus.html). While we may not be able to pinpoint the exact species, this doesn't stop us from appreciating the unique character that these blue mussels give to the rocky coast. When submitting to iNaturalist, you can identify them as "Blue Mussel Complex (Complex Mytilus edulis)" as a catch-all category that encompasses the three possible species.

Keep an eye out for the occasional golden-brown mussel - these are the same species as the blue ones, just a colour variation.

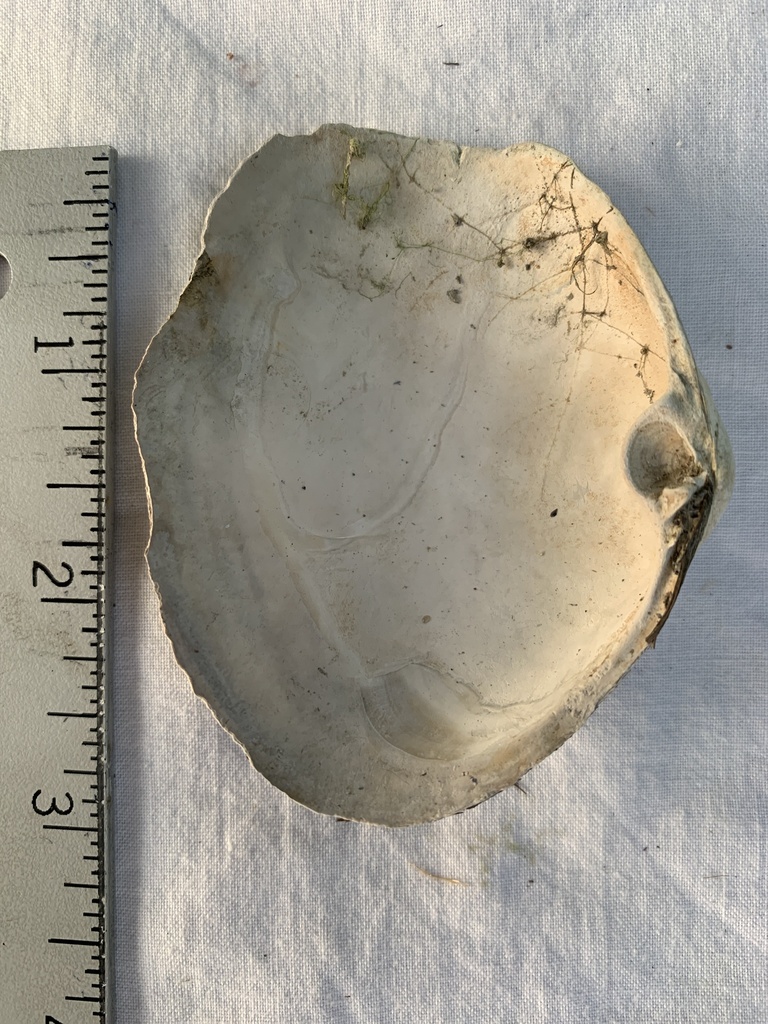

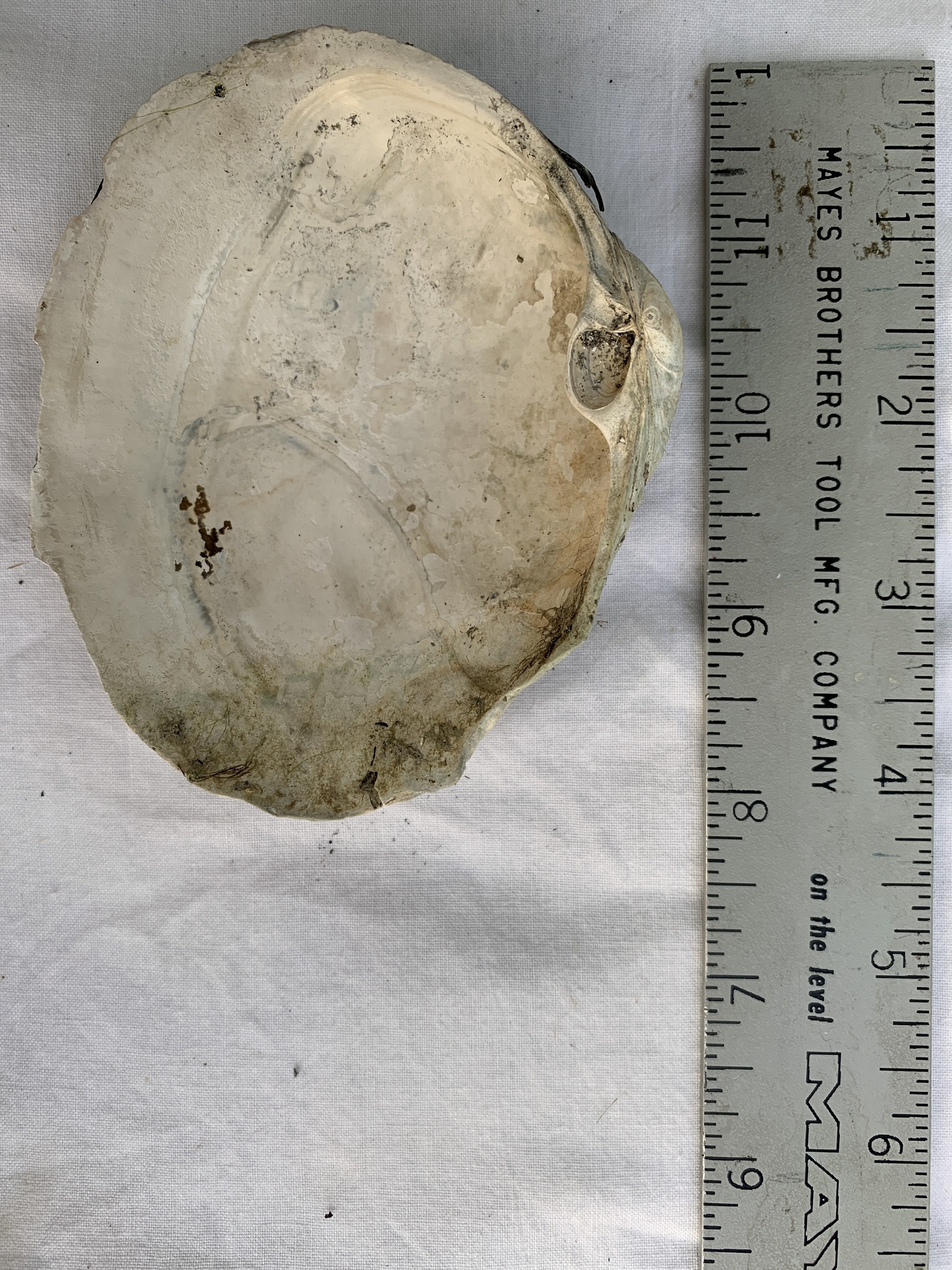

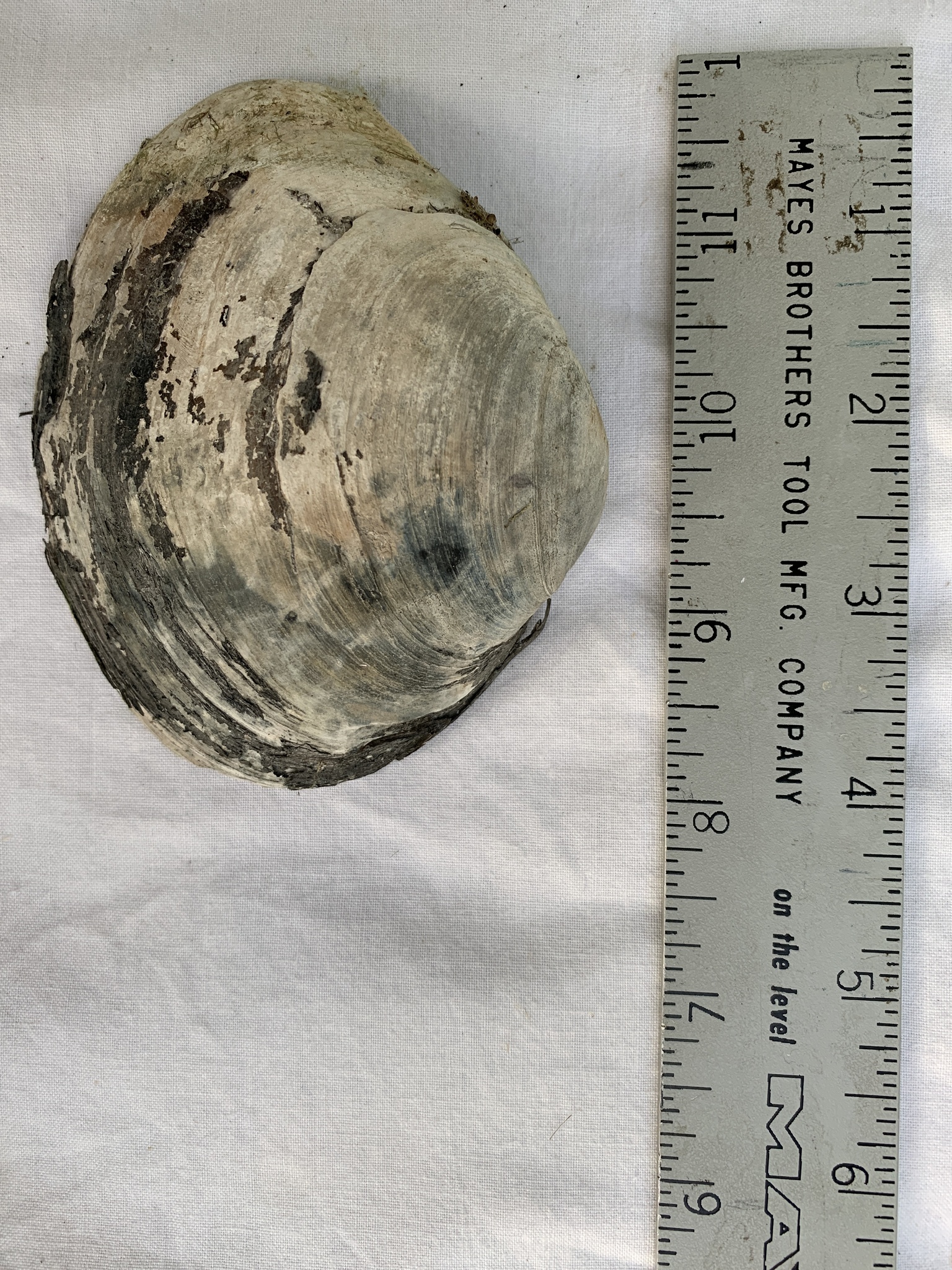

Pacific Oyster

The Pacific Oyster is a common sight on Keats Island's rocky beaches. They live their lives with one side of their shell tightly plastered against the rock they are growing on, and so they can grow into rather unusual shapes. The edges and top of the shell are wavy, and grow in flaky layers. The inside of the shell is pearly white. Their unusual shape makes them distinctive from our other Keats Island seashells. While it has not been recorded on Keats Island before, local beachcombers should keep an eye out for any possible Olympia Oysters, a much less common native species. Olympia Oysters are much smaller than Pacific Oysters - only up to 9 cm - but identification is tricky. You can learn more here: https://wdfw.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2023-08/psrf-olyguidefinal.pdf

Nutall's Cockle

Arguably one of the most distinctive shells on the Keats Island shoreline is Nutall's Cockle. These cockle shells can grow very large - about the size of an adult's fist - but you can also find tiny ones. They sometimes form distinct growth rings across their shells, allowing you to estimate the age of the animal by counting the rings like a tree. Cockles tend to live in deeper water, so most of the ones we find on the beach will be empty shells except at the lowest tide. When we see them out of water, they may look like static shells, but when the live animal is under the water and unstressed, it peers out at the world with eyes on tentacle stocks, and has the ability to jump away from danger with a strong muscular "foot".

Nuttall's Cockle can be distinguished from other Keats Island shells by its distinctive deep ridges that run down the length of the shells and cause the rim to look bumpy. Littleneck clams can also have ridges, but never as deeply grooved as Nuttall's Cockle. Even very small young Nuttall's Cockles still have these distinctive grooves.

Littleneck Clams

There are two species of littleneck clams on Keats Island: the Pacific Littleneck Clam (native to the region) and the Japanese Littleneck Clam (an introduced species). Both species live buried under the sediment in the intertidal zone, so live animals are uncommon to see, but their empty shells are abundant on our beaches. They are medium size shells that are usually white to grey, and may have mottled markings. They have ridges that run down their shell like a cockle, but these ridges are not nearly as deep and distinct as Nutall's Cockle.

Japanese and Pacific Littleneck Clam are vey similar, but can be distinguished by three subtle features:

1) Pacific Littleneck Clam tends to be more rounded, while Japanese Littleneck Clam tends to have a bit of an indent beside the shell's hinge that makes it look more asymmetrical. This takes a bit of practice to notice and is best appreciated by seeing the two species side-by-side.

2) Pacific Littleneck Clam has bumpy "teeth" along the inside of the rim of the shell. These are very small, but can be felt by running your finger along the edge if the shell. Japanese Littleneck has a smooth edge without these bumps. Keep in mind that old, worn-out shells of the Pacific Littleneck can sometimes have the teeth worn away.

3) Japanese Littleneck Clams usually have a purple shine on the inside of their shell, which Pacific Littleneck lacks.

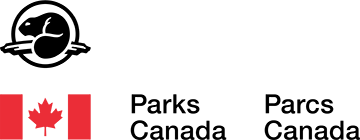

Take a look at the range of shapes and colours on these Japanese Littleneck Clams from Plumper's Cove. The freshest ones have purple interiors, but the older ones have faded to white.

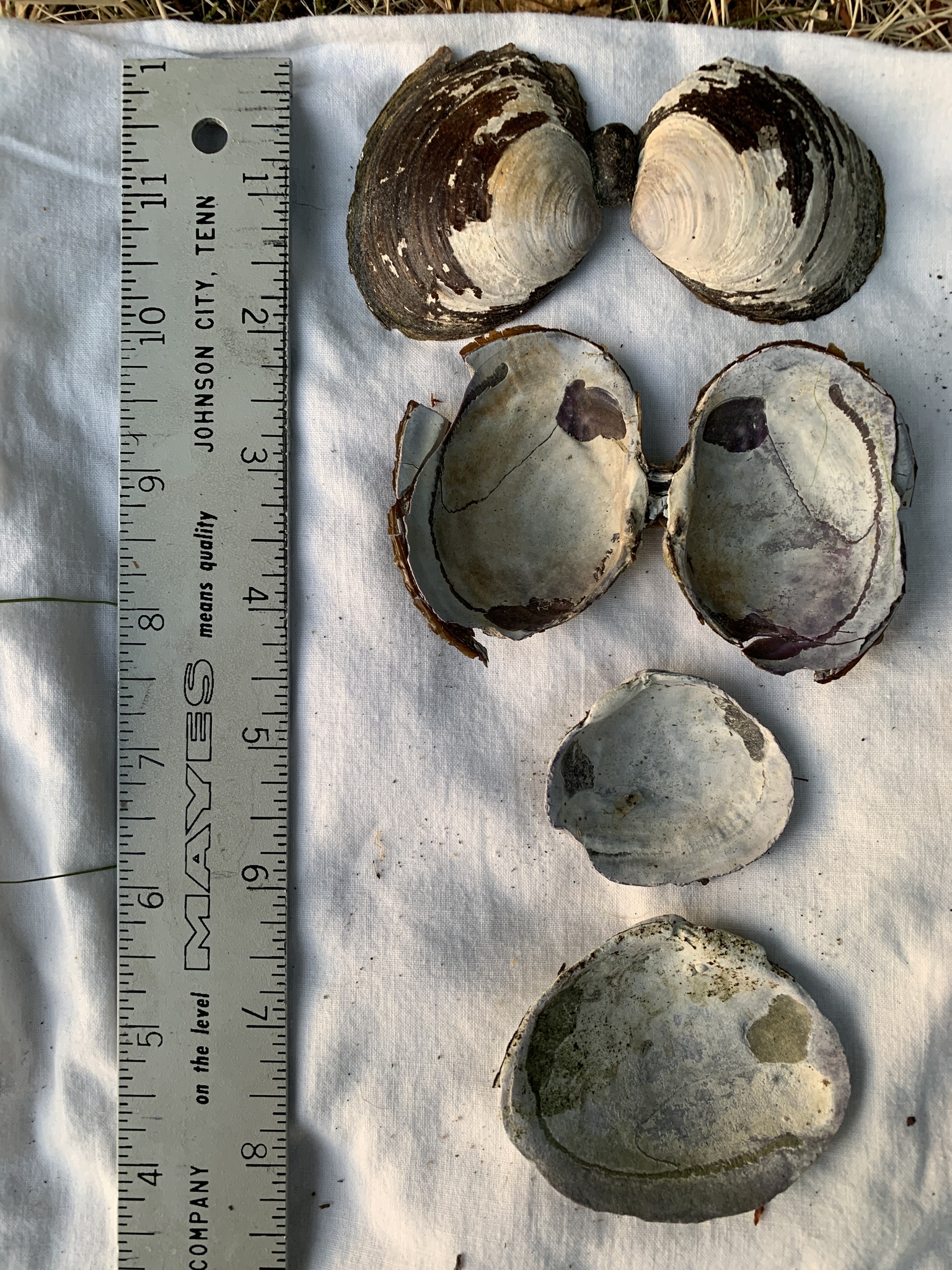

Here is a closeup of a living Japanese Littleneck Clam. When the shell is together, the indent looks as though someone pressed the shell in with their thumb to one side of the hinge. While subtle, this is enough to identify living clams without needing to see the colour and teeth on the inside of the shell.

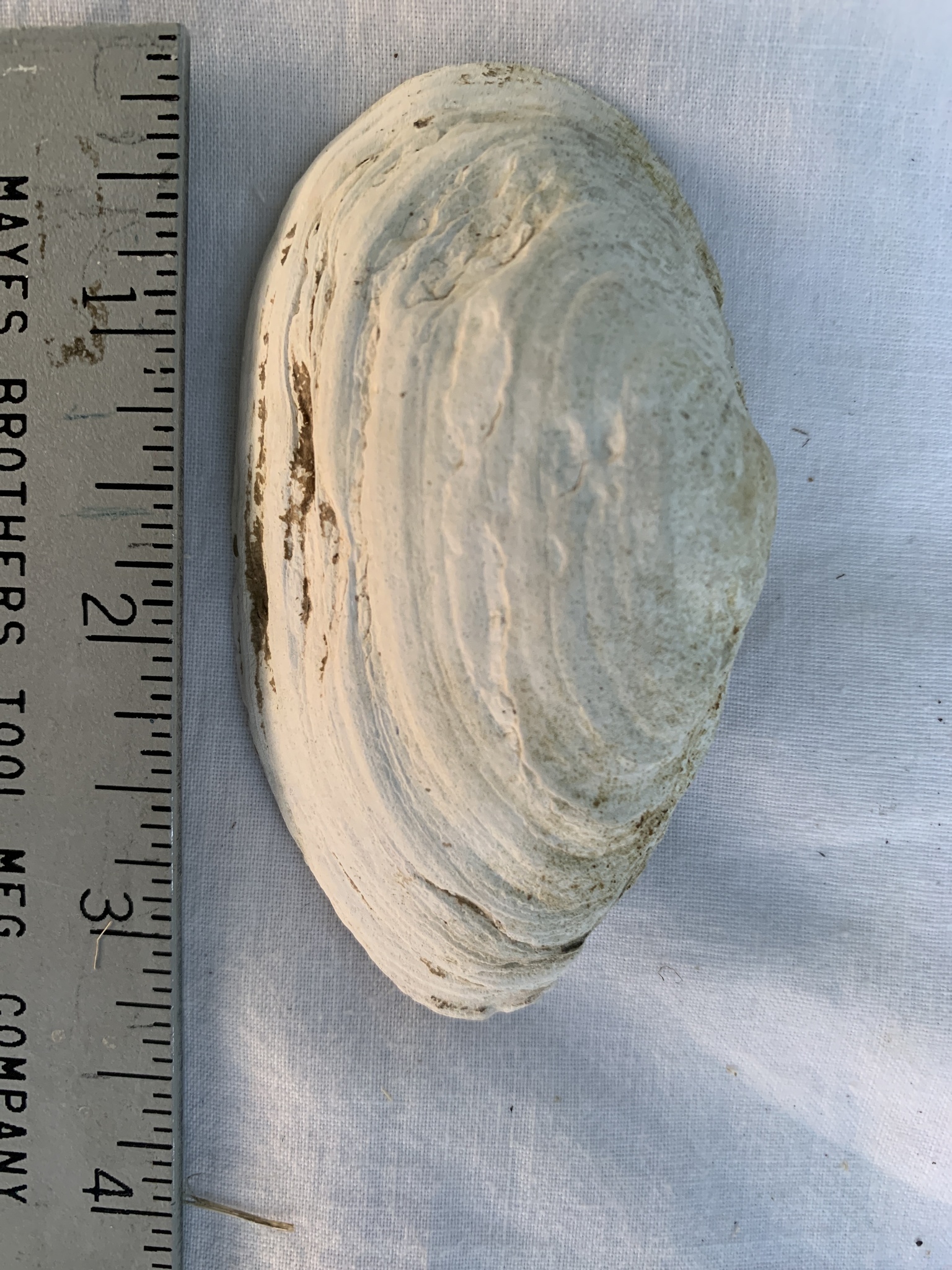

Compare the shapes above to the Pacific Littleneck Clam, which is more round with less of an indent. Instead, the shell is straight where it would be indented on the Japanese Littleneck. Can you spot the tiny ridges of "teeth" on the edge of the shell?

Purple Mahogany Clam

This distinctive species is abundant on our beaches. Originally from the other side of the Pacific, it was accidentally introduced to our area by ships. It can be quickly distinguished from our other clams by its distinctive colour: purple-violet on the inside and brown on the outside. The brown layer on the top peels off like the bark of a birch tree, revealing greyish-purple shell underneath. Even when the colours have faded, this shell is distinctive in its thin, flat shape.

Soft-shelled Clam

The Soft-shelled Clam is named for its thin, weak shell. They can be found on our beaches wherever there is a muddy seafloor for them to burrow into. They can grow large, but their shells are not particularly strong - they rely on hiding in the mud to protect themselves. Their shells are whitish, narrow, and elongated. One end is able to close, but the other has a gap where the animal sticks out. They can be distinguished from our other common clams by their long shape, weak shells, and asymmetrical sides. A surefire way to recognize them is by inspecting the hinge on the inside of the shell. One shell has a tall flat flange sticking up, and the other shell has a flat area where this flange can interlock to keep the two halves of the shell together. This structure is unique - compare the photos of the hinge to the otherspecies in ths guide.

Fat Gaper and Butter Clam

Fat Gaper and Butter Clam are our two species of large clams with strong shells. They can grown much larger than littleneck clams! At first glance, the Fat Gaper and Butter Clam can be tricky to tell apart, but one key is to look at the hinge on the inside of the shell. The Fat Gaper has a deep hollowed-out circular indent where the muscles of the live animal would have attached. The Butter Clam doesn't have this circle - instead it has tooth-like points in the hinge that stick up, allowing the two sides of the shell to lock together. These clams normally live their lives buried deep in the mud, with only the tips of their muscular siphons sticking out to filter food out of the water.

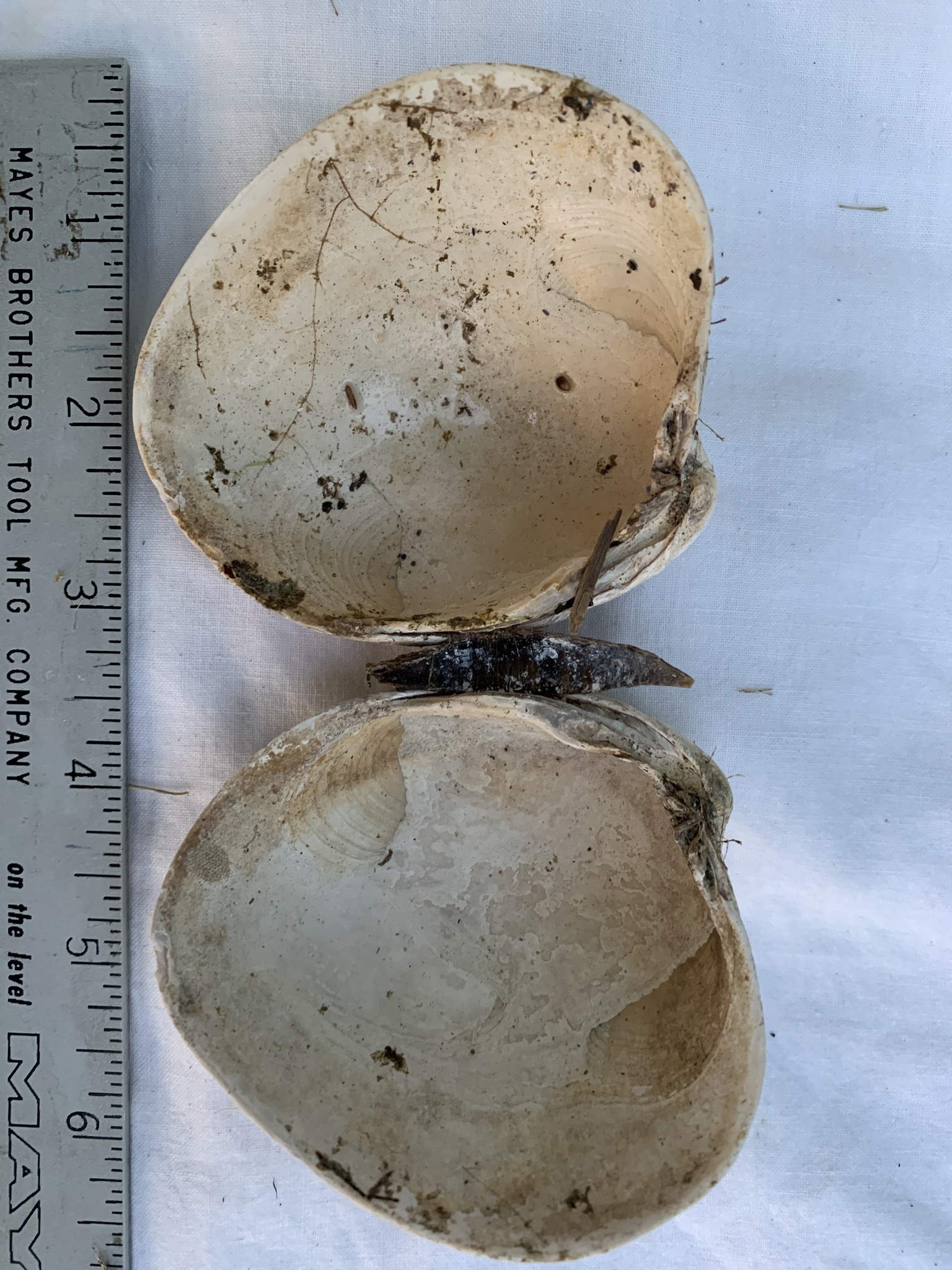

Here are some Butter Clams - they don't have the circular indent on the inside of their hinges

Compare the above Butter Clams to the photos of Fat Gapers below. Note the circular indent on the inside of the Fat Gaper's shell near its hinge. Note also that the shell does not sit flat - there is still a gap where the animal would have stuck out.

Keep an eye out for a lookalike species - there is another species called the Pacific Gaper that has not yet been recorded on Keats Island (to my knowledge). It is extremely similar to the Fat Gaper but is more elongated - it is more than 1.5 times longer than it is wide (vs the more circular Fat Gaper) and it is more asymmetrical (the "beak" of the shell is near the middle in Fat Gaper, but off to one side in Pacific Gaper) [source with more info: https://inverts.wallawalla.edu/Mollusca/Bivalvia/Veneroida/Mactridae/Tresus_capax.html]

Frilled Dogwinkle

This large sea snail hunts barnacles and mussels on our rocky shores. Its large, spiralling shells are distinctive amongst the Keats Island fauna.

Littorina periwinkles

These tiny sea snails are very abundant on the rocky beach of Keats Island, where they often cover the rocks. There are much smaller than dogwingles. There are at least two species of Periwinkles on Keats Island: the Checkered Periwinkle and the Sitka Periwinkle. The two are similar, but Sitka is stouter, and is ringed by bumpy ridges around its shell.

Limpets

There are three common species of limpet om Keats Island: the Shield Limpet, Mask Limpet, and Plate Limpet. All three can be found grazing on the rocks and cliffs on the Keats Island beaches. When underwater, the limpet slowly crawls over the rocks, scraping algae with its tongue-like radula. When the tide goes out, they cling tightly to the rock or shell that they find themselves on, waiting for the water to return.

[photos pending]

The Mask Limpet (Lottia persona) is a large species with an inflated look, caused by the sides being convex (bulging outwards). The highest point of the shell is off-centre, towards the end where the animal's head would stick out. This species is taller than the Plate Limpet: Mask Limpets are more than 1/3 as tall as they are long, while Plate Limpets are less than 1/3 as tall as they are long. Like Plate Limpets, the inside of empty shells have a dark spot in the middle, and a checkered pattern around the edges.

The Plate limpet (Lottia scutum) is a short, flatenned species. The highest point of the shell is just slightly off-centre towards the end where the animal's head would stick out. It tends to be oval, being longer than it is wide. Like Mask Limpets, the inside of empty shells have a dark spot in the middle, and a checkered pattern around the edges.

The Shield Limpet (Lottia pelta) is similar to the Plate Limpet, but not as flat. It comes in a wide range of colours and patterns.