Loving to Learn the Grasses (and other hard to ID groups)

If you want to learn wildflowers or trees, you stride forth with a field guide, or you use a plant app like Seek or iNaturalist to identify what you find, and you’re often successful. Sadly, not so with the grasses. The plant apps aren’t much help with grasses, and there are no illustrated field guides for many regions. With 11,500 species of grasses worldwide, nearly 1300 of them in North America alone, is there any hope to learn your local grasses?

Here I show how to use iNaturalist to generate a mini-field guide to the grasses you might be seeing right now in your neighborhood. As the seasons change, you can update your field guide to catch the grasses at their most recognizable stage. I think you’ll be drawn in by the intricate and subtle beauty you’ve been overlooking all this time. Grasses are great!

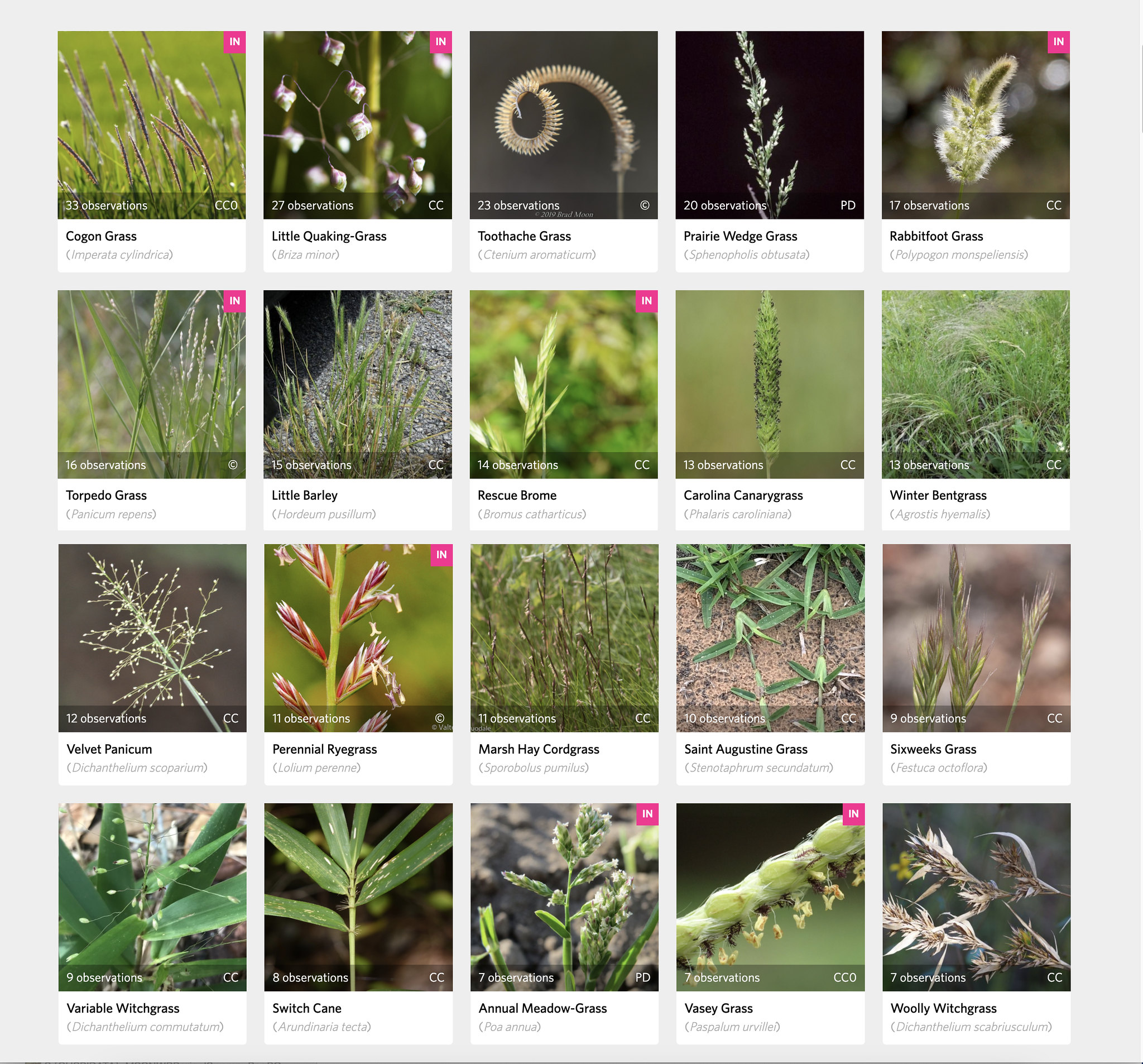

Here's an example of a guide I made for my county for spring grasses. They’re listed from the most-observed on down, so I’ve got the best chance of seeing the first several on the list.

In the guide, a pink “IN” in the corner designates species that are considered invasive, a good tip if you’re weeding your garden. The other species are natives. If you print out the guide and take it in the field with you (I put mine in a plastic sleeve with back-to-back pages), you can quickly identify a grass you come across, or at least narrow the possibilities to a few you can easily research.

So, ready to make your own mini-guide? Here are the steps.

- Go to https://iNaturalist.org on your computer (you can’t do this from the mobile app). Don’t have an iNaturalist account? This is a good time to sign up for one – it’s free!

-

Click on “Explore” at the top of the page. This takes you to an “Observations” page with search blanks for “Species” and “Location.”

-

Start typing “Grasses” in the Species blank and choose the Grasses option that comes up, and then do the same with your county or state in the Location blank. (Interested in a specific location like a national park? See the “additional hints” below.)

-

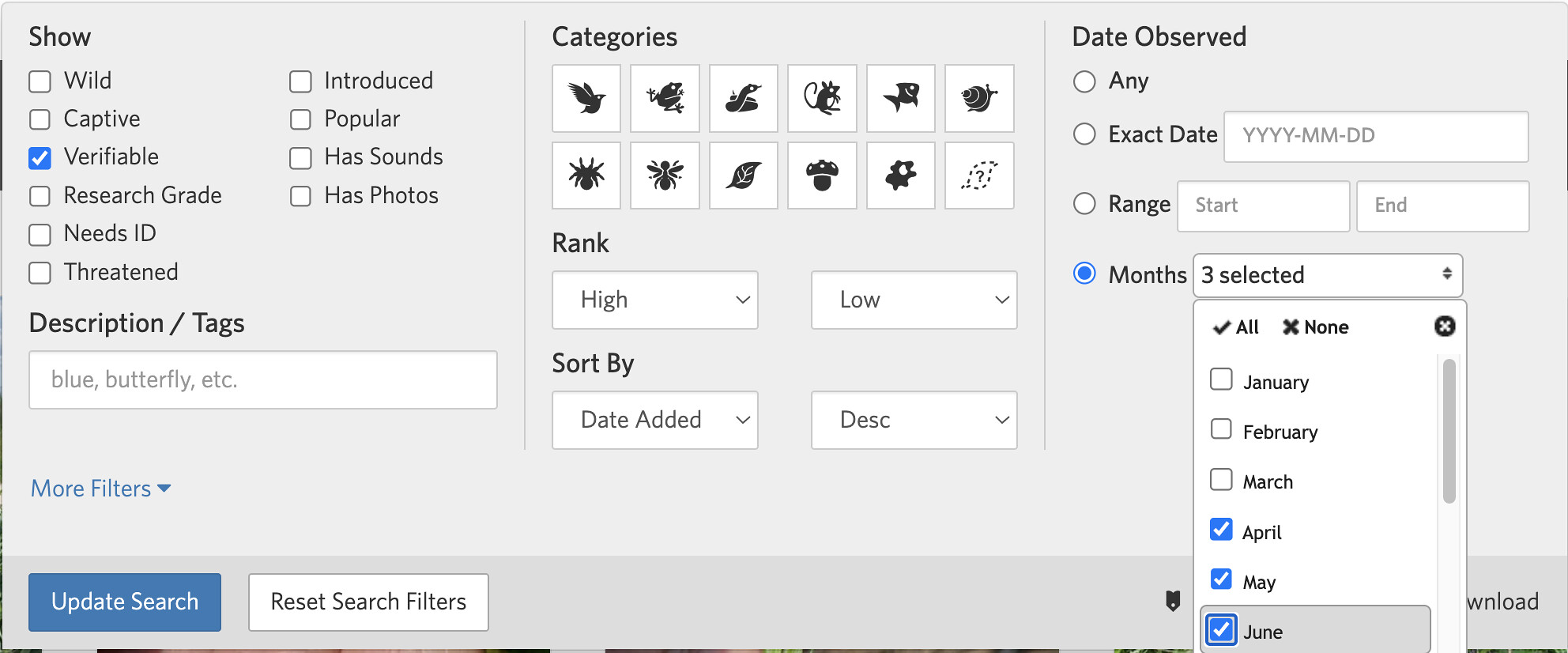

Now click on the “Filters” button at far right. This brings up a Filters panel. On the right-hand side, choose “Months” and then check one or more months that are relevant. Click on “Update search” (blue button at bottom of the Filters panel).

- You’ll see a page of observations that fit your search criteria. Now click on the “Species” tab at the top of the display. Voila! You see a gallery of the species of grasses observed in your area in the time period specified. They are ordered from “most observed” on down.

- It would be nice if you could just print this out, but if you “Print,” all you’ll get from iNaturalist is a text list of links. Instead, I screen-shot the first 10 and then the next 10 observations and then paste the screen-shots into a Word document I can print out. (If you don’t know how to do a screen-shot, google it.)

That’s it! Let’s get out there and learn some grasses! They may become your new field favorites. And while you’re at it, add some grass observations to iNaturalist to make the local guides even better!

ADDITIONAL HINTS

- To customize your guide for a particular place that’s not in the “Locations” list, use the “Filters” panel, click on “more filters,” and try typing your locality in the “place” field to see if a match comes up. Many parks etc. have been named as “places” in iNaturalist and can be used for a search.

- If you don’t get many returns for a search (just a few species observed just a few times), try broadening your search to a bigger area (like State).

- Keep in mind that not all iNaturalist observations are accurate, and ones that claim to be an unusual species for an area need special scrutiny.

- Of course, you can use this same approach to make a guide for sedges, bees, or other under-resourced groups. At this time there’s no way to narrow the search to a life stage like caterpillar, though. And for birds (like warblers or gulls), the gallery of species photos will probably be in breeding plumage, not the plumage of the month you choose.

- I love to use this approach to make a “hit list” of plants to find when I go to a brand new region. It turns a hike into a scavenger hunt. What could be more fun?