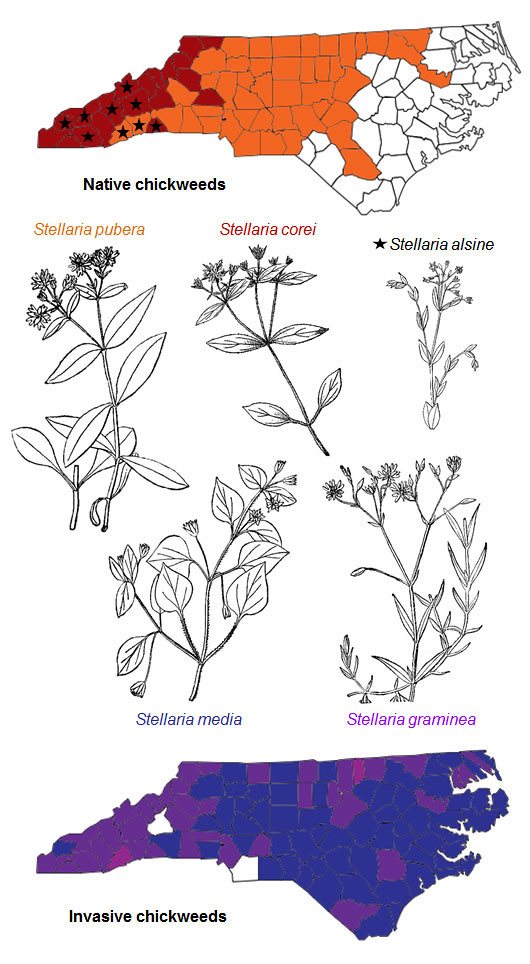

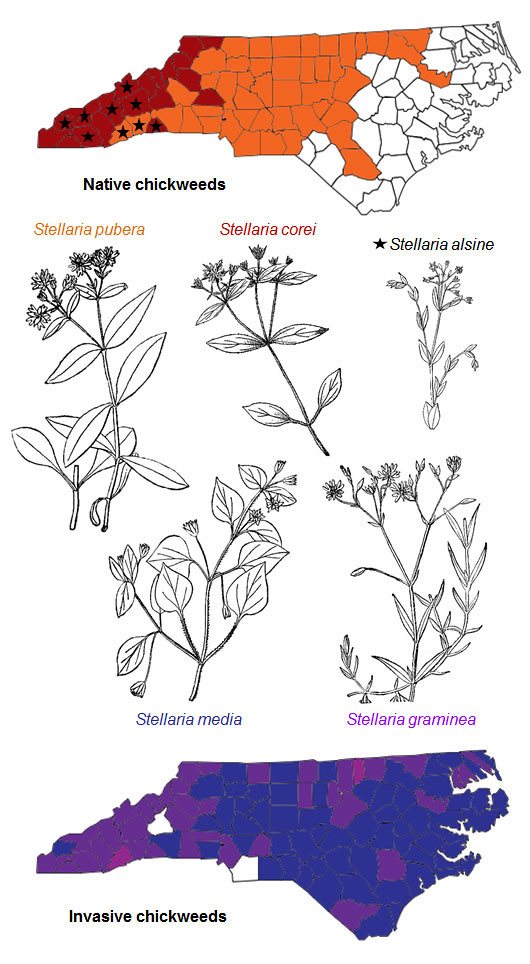

The purpose of this page is to provide an identification aid for chickweeds in North Carolina, predominantly the type found blooming in the woods in the mountains in spring. There are two genera commonly referred to as chickweeds: Stellaria and Cerastium. Here in NC, we have three native members of Stellaria (S. pubera, S. corei, and S. alsine) and two native members of Cerastium (C. nutans and C. brachypodum), with non-native and invasive species from both genera also present. This sounds like a mess to sort out, but if the goal is to identify native Stellaria it is actually fairly easy to tell these apart from the others. By far the most common one found in the woods in the mountains is the star chickweed, S. pubera.

The first step would be to distinguish native from non-native species, and Stellaria from Cerastium. If the plants are in bloom, the size of the flowers and shape of the petals is the best indicator, with different leaf shapes to support identification. As shown on the figure below, S. pubera has flowers twice the size of the others (1/2 inch across, compared to 1/4 inch) and is also known by the common name giant chickweed because of this. The characteristic that sets Stellaria apart from Cerastium is the depth of the notches on the petals. All these plants have five petals, but in Stellaria they are notched so deeply that they often appear as ten, whereas the notches don't go as far in Cerastium.

Comparison of flower size and characteristics of common native chickweed (left) and three common invasive chickweeds (right), colored in with Photoshop to make it easier to distinguish sepals and petals. The original flower pictures are from the illustrated flora by Britton & Brown, published in 1913 (now public domain), and were downloaded from the USDA PLANTS database.

A large-flowered plant found growing in the woods is most likely S. pubera. However, S. corei also occurs throughout the mountains and has similarly large flowers. The way to tell between S. pubera and S. corei when in bloom is by the length of the sepals. In S. pubera they are shorter than the petals, while in S. corei they are longer and extend past the petals when the flower is fully open. The pictures below illustrate this characteristic. Note these are young flowers that have just opened up, so the anthers are bright red. As the flowers mature, they might lose the bright color. The anthers on S. pubera stay dark, often an orange-brown, while I've seen some flowers of S. corei where the anthers were lost or not as strikingly colored.

Comparison of the two chickweeds native to NC mountain forests: The one on the left is the common star chickweed (Stellaria pubera) and was a rescue from a construction site; the one on the right is the rare Tennessee chickweed (Stellaria corei) purchased from a native plant nursery.

As mentioned above, the ranges of these two chickweeds overlap, with S. pubera common throughout the mountains and Piedmont, while S. corei is rare and restricted to the mountains and maybe upper Piedmont. Both species prefer rich forest habitats, while the third native Stellaria species, bog chickweed (S. alsine), is a wetland specialist and only occurs in the southwestern part of the state.

The maps were colored in using data from Vascular Plants of North Carolina for the native species and BONAP for the non-native ones. The plant drawings are from the USDA website and not copyrighted (original source: Britton & Brown: An illustrated flora of the northern United States, published 1913). They are scaled to each other for size comparison.

There are several non-native species in this genus and only the two most common ones are shown in the figure above. (The others are less common and more scattered.) Common chickweed, S. media, appears to occur throughout the state, with gaps in the occurrence data probably due to underreporting rather than an actual absence in those counties. Grass-leaved chickweed, S. gramineum, is also wide-spread. Besides differences in the flower size and their propensity to grow in human-disturbed areas, the shape of the leaves is another way to tell the invasives from the natives. S. media has more heart-shaped leaves, and S. graminea has more grass-like leaves compared to the natives.

No discussion of chickweed would be complete without at least mentioning the second genus, Cerastium, commonly referred to by the name chickweed. As explained above, these can be distinguished from Stellaria by the less deeply notched petals. The most common native species to encounter from this genus is nodding chickweed, C. nutans, which is fairly common in rich woods in the mountains and rare in the Piedmont. The second native species, S. brachypodum, has only few reports in the state so far and may have actually been introduced.

The maps were colored in using data from Vascular Plants of North Carolina for the native species and BONAP for the non-native ones. The plant drawings are from the USDA website and not copyrighted (original source: Britton & Brown: An illustrated flora of the northern United States, published 1913). They are scaled to each other for size comparison.

There are at least five non-native Cerastium species in the state and only the two most common ones are shown in the figures above. These are invasives of disturbed areas and distributed throughout the state. Gaps in the occurrence data are probably due to underreporting rather than an actual absence in those counties. Other non-native species are less common and more scattered throughout the state. All of these would mostly occur in human-disturbed areas, such as roadsides or as garden weeds. Sticky chickweed (C. glomeratum) is an annual weed covered in sticky hairs and with sepals extending beyond the petals, whereas mouse-ear chickweed (C. fontanum) is a mat-forming perennial with stolons that root where they rest on the ground and has sepals shorter than its petals.